The New Galleries for the Art of Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia was opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2011. The gallery houses many artifacts, artworks, beautifully intricate pieces, and a permanent installation piece titled “Patti Cadby Birch Court.” This installation is meant to be a Moroccan court to heighten interest in and appreciation of the culture and its beauty in relation to Islamic principles and art. At first, this may seem like an altruistic project for the Metropolitan to take on. Realistically speaking, though, when looking at it through a lens of acknowledging orientalism and everything that it entails, we begin to see the faults of the exhibit and how it feeds what it is trying to counteract.

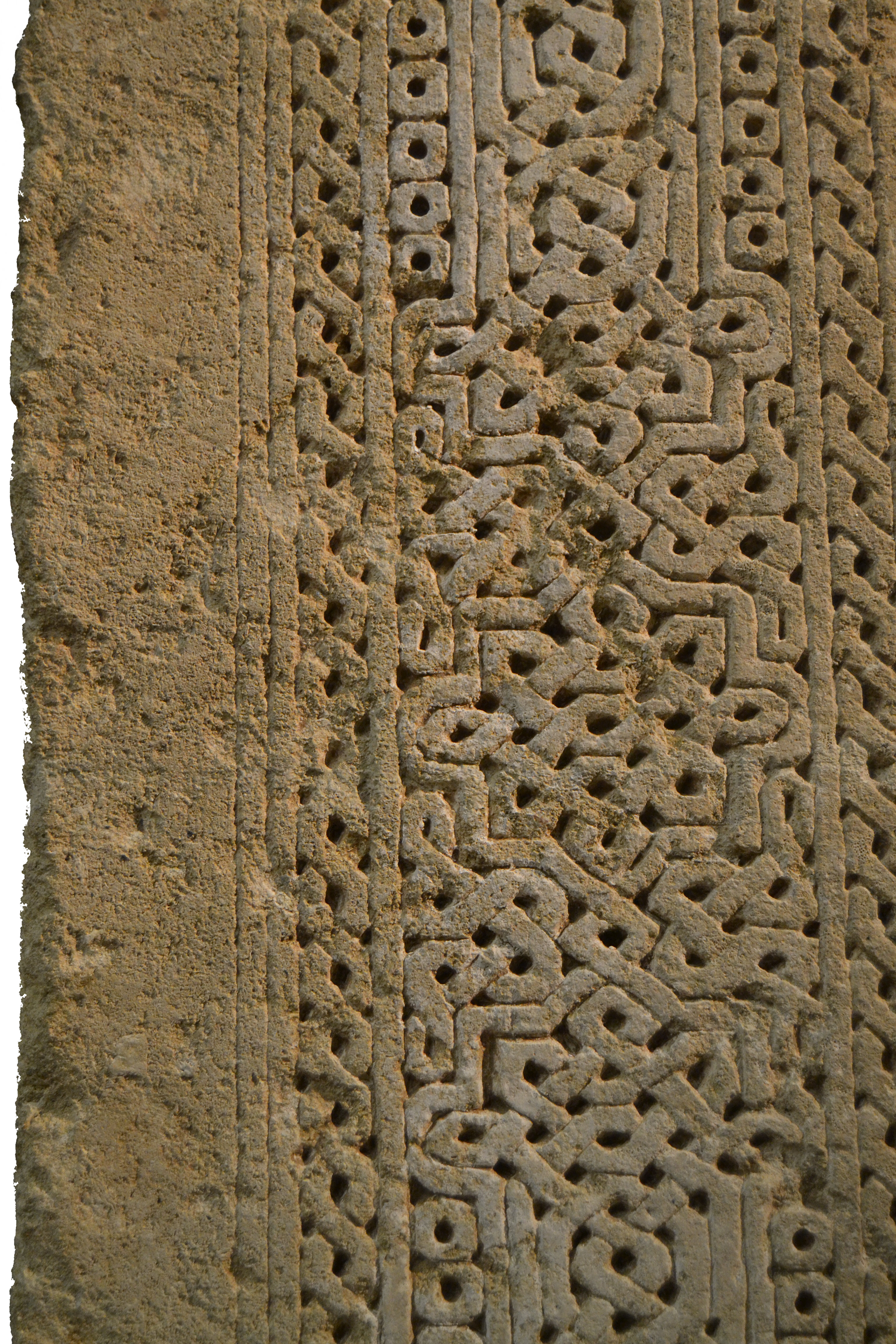

In a New York Times article describing the installation, Kennedy describes the production of the space to be an ordeal where “an Arabesque specialist in this kind of painstaking mosaic work, known as zellij, sat cross-legged, placing some of the final pieces into the arrangement with tweezers as another scattered dry grout between the tiles” (Kennedy (n.d.), 2011) (figure 1) all for the hopes of creating a “kaleidoscopic color and tessellated patterning meant to transport visitors from Fifth Avenue to Fez.” (Kennedy (n.d.), 2011) The detail of the craft is time-intensive, intricate, niche, and precise to regard beyond belief. So few people living in the modern era still know how to produce such an art, and even fewer are willing to invest in it. Even Adil Naji- an expert and inheritor of the craft- describes the work as “‘too time-consuming, too cost-prohibitive” and no longer done in Morocco. (Kennedy (n.d.), 2011) This may be a reason why although the Metropolitan typically focuses on the work of dead artists, the Metropolitan found it worthwhile to have this installation created by living craftsmen displayed in their permanent collection. (Kennedy (n.d.), 2011) Although not a dead art, a true Moroccan-style court is a dying art. This is also rationalized why there was such a focus on recreating the art accurately in even the most minute sense. When creating the patterns, “the tiles had been shipped from Fez, where large pieces had been fired in ovens fueled with olive pits and sawdust and then hand cut into individual shapes by 35 workers over a period of four months.” (Kennedy (n.d.), 2011) (figure 2) A multitude of scholars, historians, investors, and craftsmen went into making the court what it is without “‘any intrusions of modern interpretation.’” (Kennedy (n.d.), 2011)

While the amount of detail and effort that went into creating this court true to its art form is commendable, it is important to question why it happened. Why put so much time, effort, money, and accuracy into the implementation of a space typology and design. If you were to ask Randy Kennedy about his interpretation of the purpose of the space, he would say that the means of the space’s function is “not only as a placid chronological way station for people moving through more than a millennium of Islamic history but also as a symbol, amid potent anti-Islamic sentiment in the United States and Europe, that aesthetic and intellectual commerce remains alive between Islam and the West.” (Kennedy (n.d.), 2011) So this means not only is it a typical means of displaying history- as a museum is expected to do- but a display of the artful nature and intellect that comes from the Islamic art culture and how it, in turn, translates to an exchange of knowledge between the “Orient” and “Occident.” The mentality that goes behind trying to display something “orient” as something beyond the characteristics assigned to the term goes the full circle of what is trying to be counteracted; although this depends on how you define the terms “Orient” and “occidental” and what the two ideas entail. For the sake of this paper, we will be looking at Said’s interpretation of the terms.

Said himself begins his writings by explaining how “Orientalism [means] several things, all of them, in my opinion, interdependent … Anyone who teaches, write about, or researches the orient … either in its specific or its general aspects, is an orientalist, and what he or she does is Orientalism.” (Said, 1982) This means that by looking at this “other” and being fascinated by its “otherness” is a means of contributing to the ideals in which the installation is trying to contradict. By producing this $50 million endeavor, it almost fetishizes this “other” rather than fearing it. At base we must acknowledge that “the Orient is not an inert fact of nature. It is not merely there, just as the Occident itself is not just there either … men make their own history.” (Said, 1982) Therefore, things are what we say they are. Trying so hard to display a Moroccan court/ Islamic architecture as something to be admired or by attempting to disassociate negative connotations to the typology only enhances the things “otherness” to an occidental society. Although a better evil of the two, this does not contest the fact that it is an evil nonetheless. The idea of orientalism and the whole principle of orientalism only exist because we allow it. We feed it by merely trying to counteract this psychologically manifested ideal by admitting its presence. Said comments on this when saying that “to believe that the orient was created - or, as I call it, “orientalized”- and to believe that such things happen simply as a necessity of the imagination, is to be disingenuous.” (Said, 1982)

Going beyond the fact that the push for the installation comes from trying to undo orientalism through the lens of orientalism and is flawed in essence, it is also important to note that regardless of the installation being counterintuitive, it is unsuccessful. The whole point of a Moroccan court is to be a grandiose, intricate, and beautiful space to spend time, relax and feel slightly overwhelmed by the beauty surrounding you. The installation was successful in being beautiful and intricate but missed the mark on every other key point. When walking through the Metropolitan “Patti Cadby Birch Court” Moroccan Court, something with such a strong and powerful name, there is little to no emotion evoked. You feel nothing. It is uninteresting, misplaced, and unprovoking. If not given a reason to stop within, the court becomes nothing more than an intricately ornamented hallway. If the court's goal was to highlight the beauty of the architecture, then the typology needs to be accurately represented beyond just its detail. The importance put into the details of the court makes it seem as though that is all it is- eye candy- which is simply not true. The court is meant to be a space with all of the features highlighted in the Metropolitan's installation, but if it is not a space on its own, to begin with, then everything beyond that fact is lost. The installation’s placement allows it to become something you pass through rather than try to experience. Therefore, even when trying to create something beautiful and awe-inspiring to catch visitors’ gaze, the installation fails again.

Through a lens of contradicting orientalism, cost, and efficiency, the Moroccan court doesn't measure up to the commendable amount of effort that went into it. Being so aggressive in the implementation of the court is counterintuitive to repressing the orientalist views. Being so harsh and accurate to the art form in terms of implementing the typology goes against being cost-effective. Yet, it is taken and placed within something else rather than devoted to its deserved space. If willing to invest the time into the installation to have it be accurate, then there is no point in not doing it to the fullest extent and making a court.

figure 1